The first time I distinctly remember being catcalled, I was twelve. I was practicing for the school track meet, running laps around the block as the summer sun set. I was wearing tie-dye and my long blonde ponytail swayed side to side as I ran. I don’t remember what was said, I don’t even recall who said it, just the way it made me feel. It was upsetting, obviously, I felt unsafe, weird, confused. But more than that, I liked it. I don’t know if like is really the right word, maybe craved makes more sense, but I ran around the block more times that night than ever before, willing it to happen again. I threw up from exhaustion when I got back home. For some reason, there were fireworks that night. I sat on the side of the river with my family, wearing my tie-dye shirt, sensing that I was somehow different now. That I had been marked as a woman. I wished I could see myself through the eyes of the men who had yelled at me, did they think I was beautiful? Mysterious? Did they want to love me? Or to hurt me? Did the distinction between the two really matter to me, or did I just want the attention?

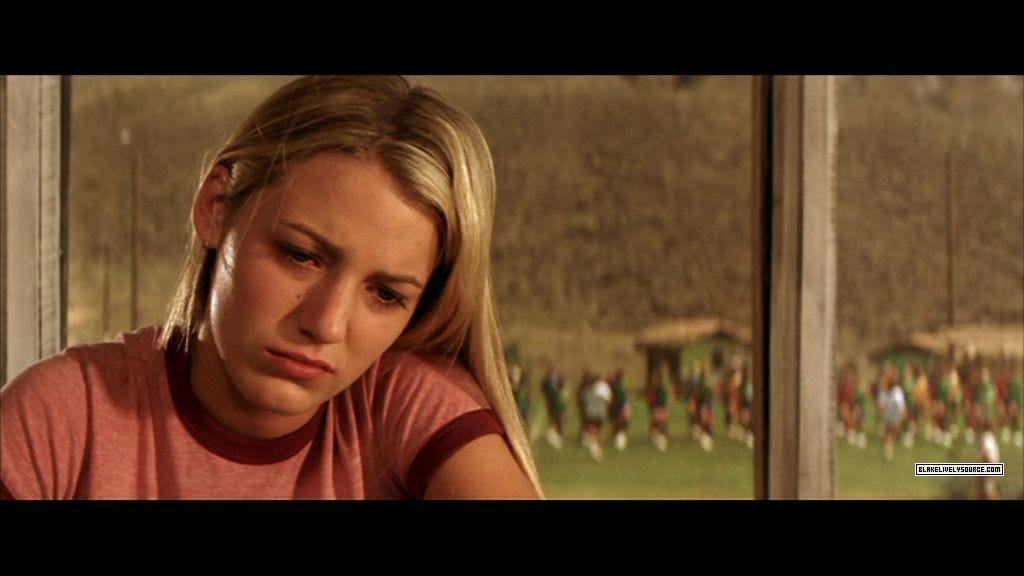

I often wonder who taught my child self how to feel? At this point in my life, nothing bad had really happened to me, but I so hoped that it would. Is there a name for this feeling? Did I just want to be special? In my little world of unremarkable girlhood, did I need to become different? Why was the only way I knew how, to hurt? In 2005, The Sisterhood of the Travelling Pants came out and it quickly became my comfort movie. I tore through the books, needing more and more of these girls who felt like my friends. I was a Bridget, of course. Beautiful, athletic, long blonde hair, a dead mom (I didn’t have that part but it sort of felt true anyways) and a deep well of sadness. My fascination with Bridget, did I know we would travel down similar paths? Or did I wander down those paths simply to feel closer to her?

I wish I could go back in time and deconstruct my personality during those formative, pre-teen years. Who was I really? Did I have an identity, or was I just bits and pieces of characters I yearned to be like? In the novel, a therapist describes Bridget as, “single-minded to the point of recklessness” and this has stayed with me ever since. I too, am single-minded to the point of recklessness, but which came first? The single-mindedness that I so strongly identify with, or the quote that I read? In the first book, Bridget goes away to soccer camp in Baja California, and she meets an older boy, Eric. He’s only in his early twenties but to Bridget’s sixteen, he is far too old for her. I recreated this relationship the summer I turned fifteen with multiple older camp counsellors. It felt like manifestation, I wanted an older man to see me as worthy of his attention and then it so suddenly happened. Just as soon as I looked his way, we were sneaking into the forest along a dirt path to the broken down gazebo, Nathan holding my hand, so charming, so beautiful. In the stillness of the trees he pulled down his pants and asked me if I knew what squirting was. The magic didn’t last but five seconds into our alone time. In the novel, Eric is tender, loving, he worries about Bridget, he reckons with his desire for her and his want to do right by her. The two end up together years later, a healthy, mutually respectful and loving relationship. Nathan did none of these things, so I thought I had to try again.

Next came Matt, also charming, also beautiful, also older. Again, I vied for his attention. I cosplayed Bridget, I wore her confidence like a costume. I used lines from the book in real life, something I have a tendency to do to this day. Months later, after camp had ended, we met up together for coffee. I felt so adult, going for coffee with an older boy. I felt empowered, in control, I was becoming who I had spent years trying to be. He offered to drive me home, it was the dead of winter, the streets were completely silent and the snow was falling in big, heavy, flakes. He raped me in the back of his car and then threw my underwear into a back alley after he cleaned himself up. They were purple with red stripes, girlish, a signal of my youth and still, after all these years, they feel like an ironic metaphor. I remember that people walked past on the street and I felt such shame. I didn’t think Bridget ever felt this way. Again, I did it wrong. Despite my embarrassment, I told this story with pride to my friends. I remember it was almost as if I was asking a question, like I was asking, this is what I wanted right? This is what we all want?

When I think about my own teenage friendships, similar to those of Bridget, they were both challenging and loving, they were what I imagined sisters to be like. I had three best friends. A Tibby, a Lena, and a Carmen. The three of them were the only real family I had at that time. I know I must have worried them or scared them at times, struggling with both extreme apathy and reckless intensity. They watched me, the same way Bridget’s friends watched her, from the sidelines, barreling towards the next thing she swore would make her happy, only to have it render her completely broken down and depressed. I had many a Bridget-esque breakdown, my friends coming over to shower me with my favorite things, to distract me from myself. I would sit quietly, refusing to look at or speak to them. I didn’t want them to know this part of me so I routinely shut them out. I always admired how Bridget opened up to her friends, something that I felt particularly incapable of. I think of who I was trying to be at sixteen, desperate for my friends to think I was invincible, untouchable, but what did that really mean? I was searching for myself, for my purpose. “Is there world enough for me?” Bridget asks in one of the novels, something that I have asked myself over and over again. Is there world enough for me?

As Bridget aged, so did I. She hurt, so badly, about who she was and what she would become. In the second novel, she gains weight and dyes her hair a dark, muddy brown. She becomes divorced from this idea of Bridget the beautiful, the sex object, the smart, witty, vixen that turns every head. The Bridget who, so effortlessly, gets everything she is supposed to want. She doesn’t want to inhabit this body that doesn’t belong to her. I too, felt that my body didn’t belong to me. Instead of gaining weight, I lost it. Instead of dying my hair, I cut my arms. I punished my body for being so desirable. I spent these years of my life so confused, unsure if I was good or bad. I was both praised and shamed for the way I looked, by strangers, teachers, my mother, my peers. I felt betrayed when the attention I so badly wanted from men turned sour, when it made me feel small and crumpled instead of larger than life like I thought it would.

Although I left the books behind in my teens, my early twenties loosely followed Bridget’s. She had an affair, I had an affair. She ruined good things on purpose, I ruined good things on purpose. I stumbled though my life as if it wasn’t my own, making decisions solely to survive. At this point in time, my choices were entirely mine, but I still felt enslaved to the attention of men, to my body, to what men wanted to do with my body. I tried to translate this attention into power and it sort of worked. I used my body as currency, climbing the corporate ladder, scoring free drugs, making people like me and want to be around me. I used my body to communicate because I didn’t have to the words to do so. I thought I was freeing myself of my body by using it as a weapon and I worked so hard to separate myself from my body, thinking that somehow, I could spare myself of feeling its pain. I watched my encounters with men from far away, like watching a movie or a show. I felt for the girl on the screen but when the moment was over, it didn’t effect me anymore. I often described the feeling as watching myself through my own eyes, an impenetrable wall between myself and my experiences. It felt as if my body was trailing behind me, struggling to keep up or, propelling me forwards, making decisions for me when I felt powerless to. My body was both my captor and my liberator.

The last five years, my experiences or encounters with men, both consensual and not, have diminished. Partially because I began to define my sexuality in more concrete terms, because I got clean and stayed away from dangerous situations, or because I learned how to say no, but I think more so because I have aged. Is it my body language that deters men now? Is it the fact that my body is that of a woman’s and not a child? Is it my short hair? There is a feeling of emancipation that comes with aging, I can walk down the street at night, wearing whatever I want, knowing almost innately that no one will yell obscenities at me. Last year, when I turned twenty-seven, I was distraught. I no longer felt I possessed a sort of gravitational pull, men’s eyes didn’t linger on me when I passed. I didn’t have immediate control when I entered a room of strangers. I was becoming overlooked, and where did that leave me? I kept asking anyone who would listen, who am I now? Without the attention? Will I cease to exist? This year, turning twenty-eight, the question still bounces around in my head, but maybe just a little bit quieter.

Bridget’s character is immortalized at thirty years old. In the final novel, the girls reunite in Greece, ten years later and discover that Tibby has died in a tragic accident. Although the darkest of all the novels, Bridget’s final form has always felt like a light at the end of the tunnel. She begins the novel with Eric, restless and unsure of her future. She’s terrified of commitment, no matter how badly she wants to be loved, but as she grapples with another tragedy in her life, she begins to find purpose. She allows herself, maybe for the first time in her life, to feel it all. To really feel it all. She lets herself hope for her future, no longer paralyzed with fear of who she will become. Thirty year old Bridget remains a sort of life line for me, a period on the end of the sentence, that sentence being growing up. As cliché as it may sound, isn’t it what we all want? To love and be loved? To allow ourselves vulnerability, to award ourselves comfort and peace. I don’t recall in detail this last book, but I do remember feeling closure. A goodbye to this woman who we both were. A woman who never belonged all to herself, but is learning, slowly, to become who she is meant to be. A woman whose worth is not determined by her body, but instead her tenacity, her bravery, her bite, her capacity for love and for joy, and for herself.

At twenty-eight, writing this a few days after my birthday, I think about my relationship with myself and the ways I have grown, like Bridget, like my friends. We take our experiences and we choose to let them stifle us or inspire us, to control us or to free us. I think about myself ten years ago, my strange, distant sister. I think of her fear, her sadness, I wonder if she would be proud of who I became, or if she wouldn’t care to know me now. Does she still exist somewhere out there? Have I outgrown her? Does she walk alongside me in another universe? Does she ever think of me? As I embark on my twenty-eighth year, I carry her memory within me. I try to do right by her. I try to impress her. I smoke weed in the park, I cut off all my hair, I dance by myself in the kitchen. I feel her pain and I live for her joy and I hope she thinks of me, too.